Who Wants to Be Tracked?

Categories: analytics

“We value your privacy…”, the clichéd beginning of many a privacy notice. I value my own online privacy, and whenever I read that phrase as part of a website consent banner it sounds like lip service at best.

Consent banners ostensibly exist to give users control over their privacy and how their data is used. Unfortunately far too frequently these banners do neither of those things, yet they take up a disproportionate amount of the privacy discussion and compliance efforts.

Everyone is of course very familiar with these kinds of banners, especially in the EU†. These kind of banners have a 14+ year history in the EU dating back to the 2009 renewal of the ePrivacy Directive, but have recently started appearing more in the US as well. Despite an increasing number of US states with privacy laws, this sort of cookie banner is not (to my knowledge) required by any of these laws. This increase of US banners is likely due to GDPR-inspired laws cropping up in the US, and a general desire of companies to protect themselves from legal action whether those banners actually provide any liability protection or not.

When implemented properly, consent banners can serve a good purpose… though I remain bearish on them in general. I think they are unlikely to be implemented well in the US and that we should focus our privacy efforts on other things — for example data breach notifications, data sharing and deletion rules, etc.

Since these banners are the most visible part of compliance, businesses have placed an inordinate amount of attention on them. It’s hard to tell what a business’ data access management looks like, even from the inside — but it’s easy to tell if there’s a banner on the website.

Despite broad dislike of these kinds of banners and the confusion about their implementation, the number of websites with them only increases over time. Dislike for them is high enough that privacy-oriented browser Brave actually blocks consent notices altogether. Brave’s approach is NOT to automatically find the “Reject” button wherever it is hidden and press that for you, but to simply hide the box altogether and block any tracking cookies that site might set. Trust in the system is so low that the most privacy-assuring way according to Brave is to flush the entire thing.

This lack of trust is rooted in broken implementations and dark patterns, where sites implement the rules in ways that are very user-unfriendly and counter to the spirit of the law. To date almost all sites using dark patterns have done so unchallenged by regulators. While there has been some enforcement against this bad behavior this year, including a 5 million euros fine against Tiktok, many consent systems remain poorly implemented… whether intentionally or not.

Here are some EU-based consent notices, perhaps coming to an US-based computer near you? All of these sites currently show no notice at all to US users.

Inside the EU, these banners do seem to be improving, but they are still pretty bad. In one effort to fight back against dark patterns, privacy activist group NOYB has filed more than 700 complaints against non-compliant banners within the EU. NOYB has been scanning sites to find and notify those with poorly implemented banners. This effort has shown improvements in the quality of consent banners, even among those that did not get a warning letter from NOYB.

This is good news, but there’s still a long way to go. As of October 2022 there were still around 50% of NOYB’s monitored sites without an obvious “reject” button, the most basic of dark patterns.

Even this paltry 50% compliance number is a best-case scenario. NOYB’s test set was made up of larger sites (thus with more tech resources to implement changes), they all used OneTrust, many had been notified by a privacy watchdog, and all were in the EU where there’s more threat of enforcement.

Since the beginning of these banners, sites have been working to “optimize” their accept percentages. Without broadly understood rules with actionable guidelines and a real threat of enforcement, this cat-and-mouse game will continue. Individual countries’ regulatory agencies (e.g. the CNIL in France) have been working to provide both clearer examples and enforcement, but the rules set by the EU are subject to different interpretations by country. In the US there’s not even a country-wide set of rules.

As we move towards figuring out how to handle consent in the US, I seriously question if the EU approach will work here. A state-by-state approach with varying rules for each state will not work and is a brewing compliance nightmare. Having a federal data privacy law would help, but I find it very unlikely that a US data privacy law would be as strong as what exists in the EU, and even less likely that there would be widespread enforcement.

While this may be one of my more controversial posts to date, I maintain that this focus on consent is counterproductive towards actual privacy and security. Having organizations focused for the next few years on how their “cookie banner” should look, what states they need one in, and what its functionality should actually be will be a huge waste of resources that should go towards other data privacy and security efforts. To quote Max Schrems from a New York Times article entitled How Cookie Banners Backfired, “No one reads cookie banners… They’ve become almost a useless exercise”.

Like any good analyst I like to support my opinions with data (though maybe it’s the other way around?), so I decided to run a survey to try and get a better handle on what end users actually think. I ran an online survey using research platform Prolific.co, targeted at 300 US internet users (excluding those that identified as programmers).

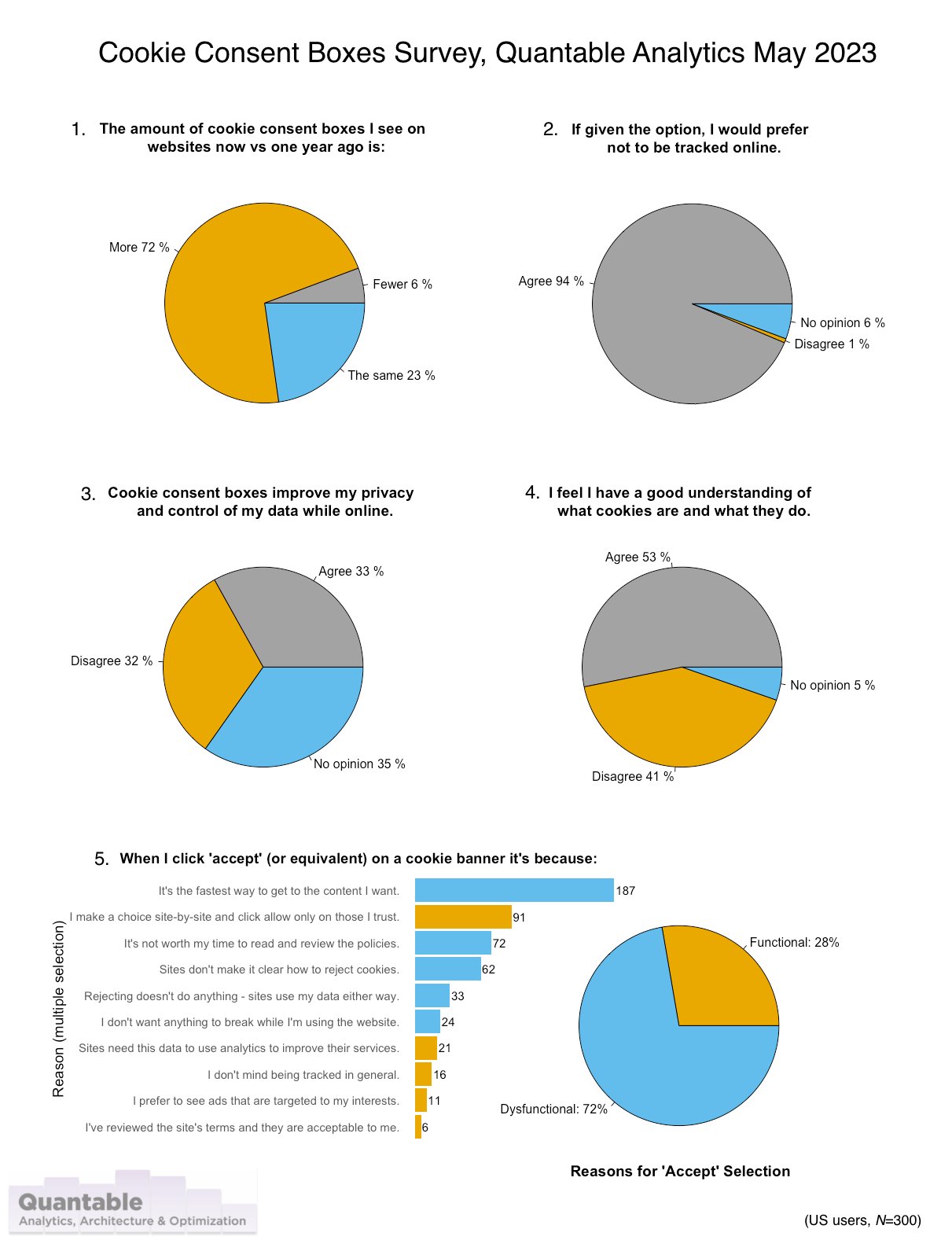

1. “The amount of cookie consent boxes I see on websites now vs. one year ago is…” 72% say more.

Again this is not surprising considering the increase in US privacy laws. There is still only 2 states (CA, VA) with active privacy laws, but there are 8 that have passed laws and 16 more with active bills (source: IAPP state legislation tracker). This survey was targeted to vetted US residents only.

2. “Given the option, I would prefer not to be tracked online…” 94% agree.

This is the crux of the matter, that all other things equal, people don’t want to be tracked. This number is similar to a claim from NOYB that only 3% of users actually “want to agree” with cookie consents. Whether it’s 1% or 3%, that’s less than the Lizardman’s constant of 4%, a good benchmark for noise in survey results.

This number makes me wonder why we even ask when most people don’t want to be tracked. Having a system with decent privacy by default assuming that everyone would click the “Reject” button all other things equal seems much more logical to me. Opt-in rates tend to increase over time. For example, when Apple first launched ATT boxes in April 2021, accept rates among US users who saw a consent banner was 12% in the first full month and then rose to 19% year later. ATT boxes are a good example to look at because it’s not possible to “optimize” the banner as it’s controlled by iOS. Some have claimed this is due to users wanting personalized ads, but I find it much more likely that friction is the reason. Basically, these repeated asks for permission become so frustrating eventually users simply give up.

3. “Cookie consent boxes improve my privacy and control of my data while online…” 33% agree.

A large majority either don’t have an opinion or disagree with that statement. Considering this is the purported reason for consent boxes, that’s not a good number. If these boxes work as intended, by definition they should at least be giving someone control over their data.

4. “I feel I have a good understand of what cookies are and what they do…” 53% agree.

This is an interesting number, and a bit higher than I expected (though in line with other recent numbers). While self-reported knowledge like can trend higher than other types of measurement, it is understandable that many users believe they understand what cookies are and what they do. After all, users get boxes on websites telling them what cookies are every day they use the web.

Certainly I don’t expect that they have any sort of deep technical knowledge about cookies, but that they do understand conceptually what they are and do. However this still means that nearly half of users don’t feel they have a good understanding, which make the idea of their “informed” consent pretty suspect. Let’s also step back from this and ask the people that write privacy policies even know what cookies are? The PrivaSeer project from PennState has a searchable index of 1.4M privacy policies. Using that corpus, the exact phrase “cookies are small text files” appears 127,472 times. But cookies aren’t small text files. Historically cookie data was stored in small text files, specifically the cookies.txt file format developed by Lou Montulli at Netscape — and perhaps it was this fact that lead to this oft-repeated phrase… but it’s not a good way to describe cookies.

Cookie data has always been key-value pair data designed to help maintain state in a browser (e.g. user_id=23 or language_pref=en_US). Modern browsers store this data not in a series of small text files but in a local database, typically SQLite. I point this out not just to be incredibly pedantic (though that is a personal hobby), but to question how we can expect users to really understand what a cookie is when so many privacy policies themselves don’t properly communicate what a cookie is. There is also a frequent conflation of third-party cookies with first-party.

I suspect that many users are actually thinking about third-party cookies when they are asked about cookies… the oft-repeated phrase that “cookies follow me around from site-to-site” only applies to third-party cookies. Despite this, I’d maintain that it doesn’t matter if users know what cookies are from a technical perspective, it matters if they understand what can be done with them. As many have said, it’s the data being captured by tracking that matters, not the underlying tech.

5. “When I click ‘accept’ (or equivalent) on a cookie banner it’s because…” 72% of selections were for dysfunctional reasons.

This is the meat of the survey, why do people actually click accept? I offered users 5 options that I considered “functional” — i.e. in alignment with the supposed purpose of consent boxes, and then 5 options that are “dysfunctional” — showing lack of trust, annoyance, etc. Far and away the most selected option with more than twice the nearest competitor was “It’s the fastest way to get to the content I want”. This aligns with the idea that you really can optimize your acceptance rates by making the “Accept” the obvious default to get to the content requested. It is interesting that the only “functional” option to receive a significant number of selections was “I make a choice site-by-site and click allow only on those I trust”. This in itself is problematic since we ask users for consent at the beginning of a session when the user may not even know yet what the website does. While this still may only be 17% of total selections it’s #2 on our list of options and indicative of the idea that users do want to treat different sites differently (as opposed to a solution like the late lamented DNT and its underwhelming rehash GPC, where preferences are set globally in the browser). Per-site opt-in is more in line with solutions like ad blockers or Firefox ETP where privacy preferences are controllable per site, which seems to be what users want.

This survey reinforced my opinion that cookie consent banners are highly dysfunctional in practice and that “consent” is frequently not informed and perhaps not even actually consent.

Consent should mean “informed consent”, but almost no users actually read privacy statements, terms & conditions, cookie policies, etc.

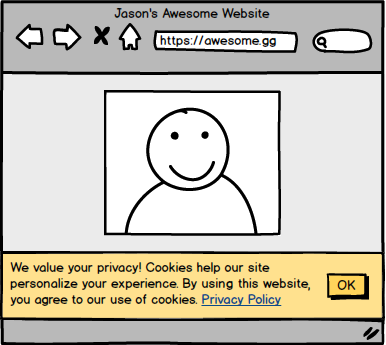

If you survey people, quite a few will say they do actually read the terms. Pew reported in 2019 that 22% of Americans will “always or often” read the terms.

This means that 78% don’t often read the terms, which is not great… but could be worse, right? The unfortunate reality is that it is much worse. Studies based on site usage show that number that don’t read the terms to be more more like 90%+.

The oft-cited “Biggest Lie on the Internet” study showed that 74% skipped over reading the terms altogether, and those that did click through to the terms had an average reading time indicating that they could not have actually read the terms (51 seconds to read a 15 minute long TOS). And that was for an imaginary social networking service where users were much more likely to be on the lookout than a typical website.

A different experiment by ProPrivacy.com had 99% agreeing to absurd terms like giving over naming rights to their first-born child. Don’t believe this? Take look at traffic for your own site’s terms of service page and see.

Terms of Service are notoriously long, and the privacy policies and cookie declarations of the big CDP providers aren’t much better.

| CDP | Cookie Declaration Word Count | Privacy Policy Word Count | |

| Cookiebot | 3,300 | 6,000 | |

| OneTrust | 5,700 | 4,900 | |

| Iubenda | 1,110 | 14,000 | |

| average: | 3,300 | 8,300 | total avg: 11,670 |

The design of the web is intended to have very little friction between interlinked documents. Cookie and privacy policies that are “required” reading up front are anathema to this design.

If I had to read the privacy policies and cookie statements for each website I used, it seems like I wouldn’t have time for anything else. Let’s do the math on that:

In the last 90 days, I visited 1,600 different websites. Admittedly this is a high number, but for a web professional maybe not so high.

If I read 300 words per minute, I’d take me 39 minutes per website. (300 wpm would be pretty fast for a technical document, but if I’m reading 1,600 of these I bet I’d get pretty good at it, at least until I went crazy)

If I read the full cookie policy and privacy policy from all 1,600 sites it’d be 1,040 hours reading policies.

That’s 11 1/2 hours each day in that 90 days (no weekends off!), simply to read the terms of the websites I visited.

Believe it or not, that’s not how I spent my last 90 days. In fact, I will openly admit that I almost never read privacy policies outside of work.

A little known GDPR provision is that all articles about cookies must include an image such as this.

Terms of use are important, but presenting a wall of incomprehensible fine print as a gate upon user’s entrance sitting right in front of the content they are looking for is a sure way to get it skipped.

Making terms more readable is a good idea, but difficult to do and still might not change people’s behavior all that much.

Sites like Terms of Service; Didn’t Read is doing good work trying to simplify terms. But their coverage of the web outside the mega-sites like Facebook is limited, and not many people use the service overall (there are 40,000 users of the chrome extension).

Users do care about privacy.

If users aren’t reading terms, are increasingly accepting cookies, and still use Facebook, do they really even care about privacy?

This is a complicated question sitting at the core of this entire discussion. My take on this is people do care, but it’s not their highest concern and they don’t feel they have control over it anyways. In the same series of polls from Pew mentioned earlier, 79% of Americans were concerned about how companies used the data they collected and 81% felt they had little to no control over that data.

This is where it’s informative to consider the intent indicated by surveys regarding who reads the terms. In other words, while the field data showed that users didn’t actually read the privacy policies, the survey data showed that they are interested in the privacy implications. I take this discrepancy to mean that people care, but that the reality of the task is that it’s simply too onerous and perceived as potentially useless anyways.

What would be a better way?

In a more ideal world I’d love to see:

- No consent banners.

- Reasonable privacy by default.

- Preferences set globally within the browser with the ability to opt-in per trusted site.

- No browsers that support 3rd party cookies (really it’s just Chrome holding this up now).

But considering that none of those things are up to me other than on my own websites, I’ll have to settle for writing this article and continuing to support organizations like the EFF.

† ePrivacy was passed in 2002, but cookie banners were part of the 2009 renewal of this legislation. Thank you to Aurélie Pols for this correction!

Outright banning third-party cookies does not make any sense, because they have their legitimate uses, and that also includes tracking and profiling users. It is not as if this is some sort of nefarious activity within the trusted mainstream actors – the privacy advocates want us to believe that, but they have not managed to point out significant problems with it.

Having said that, some things needs to be handled by individual implementations. E.g. Whether or not to record IP addresses and browser info, which also falls under the GDPR. But the API’s to handle consent should ideally be integrated in device browsers, and the fact that it is not has shown how spectacularly the GDPR has failed to properly show consideration for the interests of all parties involved. Currently the pendulum has swung a bit to far towards privacy, at huge expense to personal blogs and small websites that does not have the traffic or resources to implement consent properly. E.g. It costs much more to implement and maintain, than can be earned on AdSense.

It is also not relevant that the majority of users prefer not to be tracked, because the majority also prefers content to be free. There is a huge amount of content that would never be produced if we could not monetize it with AdSense or similar networks. Etc. Etc.

Hi Jacob, I don’t want to “ban” 3P cookies, but I would like Chrome to actually follow through with their promise to block them as Safari has now done for years. Hopefully Google will not delay that again, they have recently said they will test turning of 3P cookies for 1% of Chrome users early next year.

The thing that I hate is that I have to answer these same question on every single site I go to. I would love to see some standard around a way to answer your cookie preferences once and have those policies used by default, unless you choose to to change your default preferences for a particular site. I generally don’t mind functional cookies, or cookies used to save my settings on a site, but I reject almost all marketing cookies. This usually means I can’t just click refuse all or accept all, and have to dig through the prompts to manually turn on only the ones I want. Having to go through this process for every new site I go to is increasingly becoming tedious.

Hi Joel, I agree! Having to answer the question so many times degrades the ability to actually make a deliberative decision.

There was DNT and now GPC set at the browser level, but both of those are set for all websites without an easy way to disable per-site and with only a “yes/no” in the option. Having the default be “no highly detailed tracking” and having exclusions per site like most ad blockers work would be the best way in my opinion.

This whole thing wouldn’t be existing if the advertising maffia would not have killed the do-not-track feature in browsers and in legislation.

DNT was a good first try, though what I think killed it more than anything was Microsoft turning it on by default for everyone in IE. Which is kind of funny considering IE pioneered P3P, which was really ahead of its time.

I am still bewildered at the number of non-EU (specifically USA) sites with cookie notices. As you suggested, there doesn’t appear to be any law prescribing their presence. Unlike the 2018 Supreme Court Wayfair case which legalized “economic nexus” as a means of collecting sales tax from foreign sellers, I don’t believe the GDPR has similar overseas reach. Maybe these sites feel guilty, and even though there is no “off” switch, their consciouses feel better with the alert? Or maybe they think cookie popups are cool? If so, I can point to several browser addons and the GDPR blockers in Brave and beta (?) builds of Firefox which say otherwise. It’s all so frustrating.

Hi Alan,

IMHO, there’s quite a lot of “better safe than sorry” thinking in US legal departments when it comes to cookie banners. The GDPR has overseas reach insofar as if you’re a US site serving an EU-based customer than you’d probably need a banner to that customer. Some have said (incorrectly, I believe) that this would apply to EU citizens living in the US. They may be also thinking that consent banners are going to be required by state laws soon, or they may think that banners provide them some kind of liability protection.